The Rot Runs Deep: Illinois’ Most Corrupt Towns Lead the State in Hiding Their Books

From Springfield to the South Suburbs: When the state ignores its own audit deadlines, local governments follow suit—and the worst offenders have been hiding their finances for over two decades.

Earlier this year, City NewsWire and others reported that the State of Illinois was nearly two years late completing its annual audit. That failure set a tone. When Springfield ignores its statutory deadlines, it sends a clear message to every local government in Illinois: accountability is optional.

The latest delinquency report from the Illinois Comptroller’s Office confirms what taxpayers already suspected—local governments across the state are following Springfield’s lead, and the worst offenders are exactly who you’d expect. The 200-page document reveals that 983 local government units are breaking state law by refusing to submit their required financial reports to the Comptroller. This isn’t a new crisis; it’s a chronic disease that has been allowed to fester for decades, thriving in Illinois’ most troubled, high-crime, and corruption-plagued communities.

The Hall of Shame: Where Secrecy and Corruption Go Hand in Hand

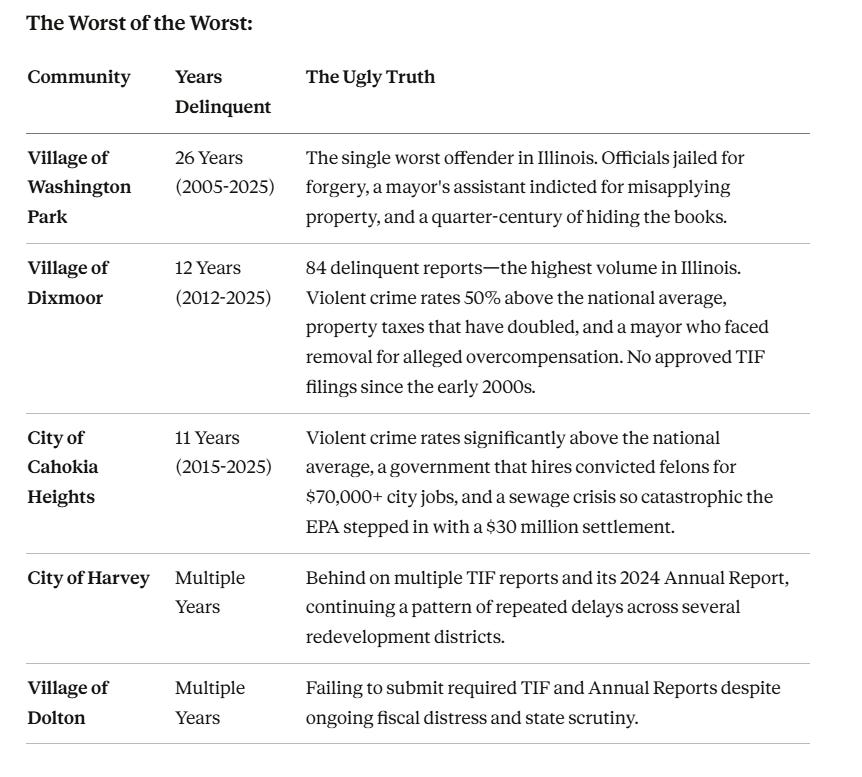

The delinquency list reads like a greatest hits compilation of Illinois dysfunction. The communities with the longest records of financial secrecy share the same characteristics: sky-high crime rates, crushing tax burdens, and a revolving door of convicted public officials. The pattern is undeniable—where transparency dies, corruption thrives.

These aren’t isolated cases of administrative oversight. This is deliberate concealment. While these governments may post a budget on their website or hold a sparsely attended public hearing, they systematically refuse to file their financial reports with the state Comptroller. This shields them from oversight and prevents the state from certifying their solvency.

The TIF Shell Game: Billions Disappear Into the Void

Tax Increment Financing (TIF) districts are supposed to be engines of economic development, redirecting property tax revenue from schools and parks to fund infrastructure and business growth. They are also supposed to be transparent. Illinois law mandates that every TIF district hold an annual Joint Review Board (JRB) meeting within 180 days of the end of the municipal fiscal year. The JRB—composed of representatives from all the taxing bodies whose revenue is being diverted—exists to provide oversight on behalf of taxpayers.

But the JRB can only review what is reported. The Comptroller’s report reveals 617 missing TIF reports across Illinois, including chronic offenders like the Village of Dixmoor, the City of Harvey, and the City of Waukegan. When a municipality fails to file its TIF report with the state Comptroller, it’s not just skipping paperwork—it’s circumventing the entire oversight process. If they are not filing the annual report, they are probably not having the meetings either.

Those diverted tax dollars can become a slush fund. In the Village of Dixmoor, which hasn’t filed approved TIF reports in over 20 years, the lack of transparency is staggering.

The State’s Toothless Threat: The ‘Do Not Pay’ List

The Illinois Comptroller maintains a “Local Government Delinquency—Do Not Pay List” for government units that fail to file required reports. The Comptroller has statutory authority to withhold state funds from delinquent entities—a powerful enforcement mechanism that could force immediate compliance.

Being placed on this list and having state funds withheld would cripple a municipality’s ability to function. It is a powerful enforcement tool that could bring even the most defiant local government to heel within days.

And yet, for decades, this list has been more suggestion than threat. The Village of Washington Park has ignored the law for 26 consecutive years with virtually no consequence. The Village of Dixmoor has hidden its TIF spending for over two decades. The state has enforcement mechanisms available but has chosen not to use them aggressively. This inaction makes Springfield complicit in the secrecy and the resulting corruption.

Not Just the Usual Suspects: Even Wealthy Communities Are Hiding

This isn’t just a problem in struggling, high-crime communities. Even some of Illinois’ wealthiest suburbs are on the delinquency list. The Village of Deerfield, an affluent North Shore community with a median household income over $150,000, has failed to file TIF reports for its Downtown Village Center district for both 2023 and 2024. The Wilmette Public Library District, serving one of the most educated and prosperous communities in the state, is delinquent on its 2025 Annual Report.

If even wealthy communities with professional staff and ample resources can’t be bothered to file their reports on time, the problem isn’t just capacity or resources—it’s a systemic disregard for transparency that has infected governments at every income level.

Lake County’s Dysfunction Triangle: A Case Study in Serial Non-Compliance

Perhaps nowhere is the delinquency crisis more concentrated than in Lake County, where three cities—Zion, Waukegan, and North Chicago—have turned non-compliance into an art form. Together, these three cities represent over 100,000 residents who have no state-verified financial transparency from their local governments.

City of Zion is a chronic violator with 25 delinquent reports, making it the 8th worst offender in the entire state. The city has failed to file Annual Reports for five consecutive years (2021-2025) and has missing TIF reports across four separate districts.

City of Waukegan, one of the largest municipalities on the delinquency list, is missing its 2025 Annual Report and TIF reports for four major districts, including its North Lakefront, Downtown Lakefront, South Lakefront, and McGaw Business Center TIFs. The city also has unresolved Fountain Square TIF reports dating back to 2021.

City of North Chicago is perhaps the most troubling case—a textbook example of systemic dysfunction. In 2019, the city’s firefighters’ pension fund was so underfunded that it triggered the state’s pension intercept law. Meanwhile, North Chicago School District 187 was once placed under state financial oversight due to its own fiscal crisis. Now the city is back on the delinquency list, missing its 2025 Annual Report and TIF reports for three districts for both 2024 and 2025.

But it gets worse. Even the Foss Park District, which serves North Chicago, is delinquent on its 2025 Annual Report. Every single unit of government in North Chicago—the city, the school district, and the park district—has either been under state intervention, has triggered the pension intercept law, and/or is hiding its financial records from taxpayers.

When Dysfunction Goes Viral: The Contagion of Fiscal Collapse

North Chicago isn’t alone in this systemic collapse. The pattern repeats across Illinois: when one unit of government operates without accountability, it sets the tone for all the others. Transparency failures spread like a disease.

The City of Harvey has three delinquent units—the city itself, Harvey Public Library District, and Harvey Park District—all while having its sales tax intercepted for pension payments. The City of East St. Louis has the city, East St. Louis Park District, and East St. Louis Township all on the delinquency list, and also had its tax revenues seized for pensions. In Cahokia/Cahokia Heights, the city, village, and public library district are all delinquent. Even the Village of Dolton, already notorious for fiscal mismanagement, has both the village and Dolton Park District failing to file.

When one layer of local government abandons accountability, taxpayers are left completely in the dark about how their money is being spent across every level of public service.

The Pension Intercept Hall of Shame

Under Illinois’ pension intercept law, enacted in 2016, pension boards can demand that the Comptroller intercept a municipality’s sales tax and other state-shared revenues if the city fails to make required pension contributions. It’s a nuclear option—a sign that a city’s finances have collapsed so completely that the state must step in to protect retirees.

The City of Harvey was the first major case in 2017, with its police pension fund winning a $7 million judgment and forcing the Comptroller to withhold the city’s state tax revenues. The City of East St. Louis followed in 2019, facing interception for $2.2 million in pension debt. Both cities are also on the Comptroller’s delinquency list for failing to file financial reports.

The pattern is unmistakable: cities that can’t manage their pension obligations also can’t be bothered to file their financial reports. Fiscal dysfunction and transparency failures go hand in hand.

A Culture of Negligence: From the Statehouse Down

The State of Illinois’ own two-year-late audit set the tone. When Springfield ignores its statutory deadlines, it tells every local government that deadlines no longer matter. That example has normalized negligence.

The issue is no longer isolated or clerical—it’s cultural. Whether it’s the City of Harvey and Village of Dolton in the south suburbs, the Village of Bensenville in DuPage County, or the City of Waukegan and City of Zion on the lakefront, Illinois governments have fallen into the same pattern: missing filings, ignoring deadlines, and eroding the public’s ability to track how taxpayer money is used.

Transparency failures at this scale don’t happen by accident. They signal a collapse of fiduciary oversight where boards and administrators stop fearing accountability because no one enforces it.

Fiduciary Duty: The Forgotten Promise

Elected officials and administrators hold a fiduciary duty to manage public funds honestly, prudently, and transparently. Delinquent reporting violates that trust as surely as misuse of funds. When governments fail to file, the Comptroller cannot certify solvency, auditors cannot detect waste, and residents cannot know how their money is spent.

Late reports don’t merely reflect disorganization—they obscure accountability. And in communities like the Village of Washington Park, Village of Dixmoor, and City of Cahokia Heights, where crime is rampant and public services are failing, the refusal to show the books suggests something far worse than incompetence. It suggests a deliberate effort to hide waste, fraud, and corruption from public view.

The Way Forward

Illinois faces a choice. The Comptroller can continue treating the Do Not Pay list as an empty threat, allowing 983 units of government to operate in the shadows. Or the state can enforce the law it already has on the books, cutting off state funds to delinquent governments until they comply.

The Village of Washington Park has been hiding its finances for 26 years. The Village of Dixmoor for 12 years. Lake County’s dysfunction triangle continues to operate without accountability. These aren’t administrative delays—they’re deliberate violations of public trust.

Public money demands public accountability. In Illinois, that basic principle has been arriving past deadline for decades. It’s time to stop waiting and start enforcing. The law already exists. The only question is whether Springfield has the will to use it.

References

[1] Illinois Office of the Comptroller. (2026, January 15). Local Government Division - Delinquent Units.

[2] U.S. Department of Justice. (2014, March 14). Former Washington Park Street Superintendant Sentenced to Prison for Forging Village Check.

[3] BestPlaces. (n.d.). Crime in Dixmoor, Illinois.

[4] Chicago Tribune. (2020, January 17). Dixmoor mayor may face removal from office over alleged $64,000 in overcompensation.

[5] NeighborhoodScout. (n.d.). Cahokia, IL Crime Rates.

[6] St. Louis American. (2021, October 17). New city, same betrayal of public trust.

[7] City NewsWire. (2026). Illinois Local Governments Following State’s Lead on Delinquent Filings.

[8] Illinois Policy Institute. (2021, September 27). Illinois’ rising property taxes driven by $75 billion local pension debt.

[9] Illinois Policy Institute. (2025, October 27). Harvey needs a way out of its crippling pension debt.

[10] Illinois Policy Institute. (2019, September 19). East St. Louis faces interception of state funds for $2.2M pension debt.